Paul Gauguin’s Eden: The Spiritual Unity of the Tahitian Land and Women

Paul Gauguin is recognized as one of the most prominent artists who contributed to Primitivist art, known most famously for paintings such as Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? and other paintings depicting the women of Tahiti. His passion for painting the people and land of Tahiti grew from starvation for a place untouched by modernization and colonization. He was entranced by the knowledge he gathered on Tahitian culture and was driven by his distress in France to find a home there. Tahiti was his idea of a feasible Garden of Eden, untouched by man, purely divine. Alas, this was not the truth behind the nation when he arrived for Tahiti was now a French colony. This modernization imposed on the land he dreamed of did not stop him from reaching towards his goal of experiencing what he would consider primitive and savage. He found some solace in the community through painting the land and people as if there had never been any colonization, the way he believes it should have always been. While he created many landscapes of this primitive Tahiti, it is the portraits of Tahitian women that cemented his legacy in art history. However, the intent of painting Tahitian women was never about the women themselves, but as spiritual beings. Through his journey in Symbolist art, Gauguin grips on to the desperation to escape Westernization and paints Tahitian women as representatives for the Eden he longs for.

Parisian artist Paul Gauguin did not conform to the common philosophy of artists in his time. He began his career in France, considered to be an impressionist alongside artists like Vincent Van Gogh and Camille Pissarro. He painted Breton landscapes and still life paintings familiar to the era and began branching out into self-portraits and portraits of women. Typically, his subject was that of familial figures, particularly his wife, women he adored, or groups of women who worked the land. With the exception of one early nude study, he never depicted nude women at this time of his artistic career (fig. 1). Two examples of his early portraits of women include that of Ingeborg Thaulow done in 1877 and that of his wife, Mette Gauguin in 1878 (fig. 2, 3).

Both paintings depict the two women in minimal detail. The impressionistic portrait of Ingeborg Thaulow depicts little realistic semblance of her true appearance. Rather Gauguin paints her at a profile turned away enough to where the viewer only sees a single, shadowed eye and the slightest appearance of lip shape. With what is distinguishable, she is wearing a collared top and possibly a small hat of sorts. Painting in such dark, neutral colors makes it more difficult to distinguish where the foreground and background end. She could very well be anyone with dark brown hair. Gauguin paints his wife embroidering depicts her in a similar effort. The lighting choices he made cast shadows upon her face that don’t appear as dark on other shadows pile that of her sleeve or table. He has dimmed her face so that she may simply be recognized as a wife embroidering versus her own individual person. The visual focus of this painting is guided towards the action of an indistinct woman embroidery rather than Mette herself. These paintings mimic Gauguin’s time spent in impressionism before he discovered his unique, more famously recognized painting style.

Paul Gauguin and Mette Gauguin had been married for five years at the time of this portrait of her. Gauguin had yet to follow his passions in art as a full-time career and to stunt the growth of his career even further, Mette did not approve of her husband going down such a path. Eleven years into their marriage, Mette had fled back to her family home in Copenhagen and he followed her where he pursued a career in cloth sales. His marriage was failing, he was in a country unfamiliar to him, did not speak the language, and hated his job. He grew so exasperated with his life that he chose to paint for a living. Driven apart by their misaligned views, Gauguin left his wife and children in Denmark to return to France as a full-time artist.

He found residency in the town of Pont-Aven in Brittany where discovered joy in the rustic simplicity that is Breton life. Paintings such as Breton Girls Dancing (1888) (fig. 4) and The Four Breton Women (1886) (fig. 5) show the effortless, trouble-free atmosphere that Pont- Aven held. The young girls, garbed in folk wardrobe, dancing around in a circle in the bright yellow, wild field mimic the pure bliss and excitement for uncomplicated life Gauguin felt in his new home. The Four Breton Women features a similar approach and also feature the beginnings of Gauguin’s taste for distinct contours and heavy coloration. His paintings show the gestalt of all of Pont-Aven compared to elements that make up the town.

Gauguin is described as being “attuned to the harmonious relationship between the inhabitants of Pont-Aven, their dwellings of granite and thatch, their animals, and the verdant countryside around them” (Pichon, pg. 48). The message Gauguin paints is to express the pure aura and primitivist atmosphere that he ever-so longs for. He is not painting to show four women conversing or anything relating to their personhood, rather he is expressing how he experiences this environment through the people and landscape as a synecdoche. These four women do have a hand in on his experience and are shaped within that painting’s moment, but these women are not the sole motivation behind the painting. They are a part of the environment as a whole, unified into the mix of everything that makes Pont-Aven a primitivist Eden for Gauguin.

Pont-Aven was not enough for Gauguin however. In 1887, he decided to abandon the life he built himself there and landed in Martinique with a friend and fellow painter Charles Laval. If he were to further grow as an artist and “live like a savage” then he had to get out of France (Crepaldi, pg. 36). Martinique exposed Gauguin to a new world of color and shape he never could have discovered in France. Nostalgia from his childhood in Peru set in upon arrival and awakened an even deeper appreciation for his new home. Ingo F. Walther states “Gauguin’s love of the tropics may have been an escapist flight from civilization, but it was also an attempt to rediscover the happiness of his South American childhood.” His parents moved the family to Peru when he was just one year old and stayed until he was seven years old. From an early age, his Eden was amongst the exotic and untouched land of his grandfather’s. When he was forced to leave and move back to France with his mother, he found extreme difficulty adjusting to urban life and French ways of society.

In 1887 when he returned as a painter, he reclaimed a bit of that primitivist joy he desired. He unexpectedly came upon a community of women who had taken an interest in him. Meeting women from a world he fetishized, who found him and his fascinating, grew into extreme temptation. When gazing at paintings such as Allées et venues, Martinique (fig. 6) completed in 1887, Gauguin’s appreciation for Martinique women becomes much like that of the Breton women but much more energizing.

Figure 6

Gauguin himself claimed “What [he finds] so bewitching are the figures, and every day here there is a continual coming and going of black women.” His fetishization of these women goes deeper than just their appearance, however. He is intrigued by their way of life, their walk, how they function, etc. Instead of being an outsider who takes what he sees for face value, he is invested and absorbs the culture to understand their “savage” life. In his eyes, the women of Martinique were primitive and more exotic than any other women he met before in his artistic career. White Breton women could never have sufficed that intrigue of the primitivist life he so desired, even if he was attracted to their rustic lifestyle because he was still in France. The unifying connection between the women and the land is what formalizes this primitive Eden in his mind.

Gauguin wrote to Mette about the women in Martinique saying “It’s not easy for a white man to hold his virtue here, for Potiphar’s wives are not lacking. Nearly all of them are dark- skinned, from ebony to dusky white. They go so far as to cast spells over fruit, which they then offer in order to snare you” (Pichon, 56). He still loved his wife despite moving to the Caribbean for his art’s sake. All the letters he wrote to her, attempting to salvage their marriage, were never reciprocated until the bitter end of his time living on the island. She wrote back to say that their marriage would not withstand any more hardships and that they should move forward apart from each other. With no hope for his marriage, he would have gloriously outlived his days in Martinique but a terrible case of tuberculosis forced him to move back to Paris, his paintings and studies left to be unfinished along with his contentment in paradise.

As the next few years went by in France, he gained friendships with some of the most famous names of the era, most prominently Vincent Van Gogh. Amidst a time of frustration with the intent of technically driven art at this time, Gauguin confided in Van Gogh that he couldn’t find importance or value in doing the same in his art. He wrote to Van Gogh, “I am in complete agreement with you concerning the unimportance of accuracy in art.” Yann le Pichon writes “The irresistible need for idealization that obsessed Gauguin from now on was symptomatic of a yearning to transcend the natural world around him” (pg. 73). Through conversation and consultation with his artist friends Émile Bernard, Van Gogh, and Émile Schuffenecker, Gauguin found a niche that he engineered for himself, Synthetism, also referred to as Cloisonnism. A branch out of Symbolism, Gauguin followed the same style motto of symbolists: “ideistic, symbolist, synthetic, subjective, and decorative” (Hollmann, 11). The Tate Museum in England defines Synthetism as “Rather than painting a naturalistic representation of observed reality, Paul Gauguin and his followers at Pont Aven aimed to create art that combined (or synthesized) the subject-matter with the artist’s feelings about the subject and the aesthetic concerns of line, colour, and form.” He is famously recognized as a Symbolist artist, apart from Impressionists, but he was more specifically a Synthetist.

Figure 7

The painting that cemented his shift into Symbolism and Synthetism was The Vision after the Sermon (fig. 7) from 1888. This painting was one of the early models for Gauguin’s interest in integrating religious context into art though large blocks of color and line. Pichon writes “Like valiant Jacob grappling with the messenger of the Lord and emerging victorious against his Impressionist elders in order to transcend the natural world” (pg. 82). He did this with the purpose of the commonly known story’s message to be emotionally felt versus factually read. Painting figures with such a severe technique and skewed perspectives takes out the reality of the situation and leave behind the emotive senses. Gauguin also stripped the setting of any contemporary objects or landmarks to revive this painting as a primitive experience. Gauguin transformed this “Vision” in this painting into his vision for what he wishes to see, a primitive Eden.

At this point in time, Gauguin had outdone his days in Arles, Brittany, Copenhagen, Martinique, and Le Pouldo; he was exhausted and drained of Europe. In a letter written to Émile Bernard, he writes “Nothing remains of all my efforts this year but a hue and cry from Paris that reaches me here and discourages me so much that I am afraid to paint anymore, and I drag this old body of mine along the shores of Le Pouldu white the north wind blows...My soul is gone.” He later writes in a letter to his wife Mette: “May the day come (soon perhaps) when I can go off and escape to the woods of some South Seas island and live there in ecstasy, in peace, and art. With a new family, far from this European struggle for money. There in Tahiti, in the still of beautiful tropical nights, I shall be able to listen to the soft, murmuring music of my heart beating in loving harmony with the mysterious creatures around me.” He had grown poor, wearisome, and desperate to return to a primitivist state away from all the stress of a growing modernization that was soon to shrink him.

The late nineteenth century brought about a new France, a modern and advanced country. Industrialization was the new empire of Europe. Railways were routed all over the country creating a large economic boom. Cottage and familial businesses were being ruined to make way for corporations. With his newfound appreciation for primitivist art styles and ways of living, he came to despise the way France had evolved into an urban civilization (fig. 8, 9). France was poisoning his ideal world of peace & tranquility; it was pure chaos and hell he had to live in. His only remaining hope for the world he longed for was for him would emigrate to the South Seas. He would leave behind his estranged wife, mistress, children, and artistic reputation in France to find solace in Tahiti.

The Tahiti he arrived at was not at all what he wanted to see. He envisioned a savage, untouched culture, but arrived in a community that had already experienced Westernization and colonization. The France he wished to leave behind had made its way to the South Seas before he could. At the beginning of his journal surrounding his time in Tahiti, Noa Noa, Gauguin describes his initial impression up arrival: “It is the summit of mountain submerged at the time of one of the ancient deluges. Only the very point rose above the waters. A family fled thither and founded a new race — and the corals climbed up along it, surrounding the peak, and in the course of centuries built a new land. It is still extending, but retains its original character of solitude and isolation, which is only accentuated by the immense expanse of the ocean.”

Gauguin gazed at the paradise of his visions from the boat that would guide him to his new life. Little did he know that this haze of untouched glory would soon dissipate. The island had become a French colony and the process of Westernization had begun. “The dream which brought me Tahiti was cruelly plied by the present: it was the Tahiti of days gone by that I loved.” The paradise he desired and believed he found was now forever lost. In his painting Mata Mua (fig. 10), Gauguin is showcasing the land as it is at birth, untouched, unspoiled, strictly native.

Figure 10

“Mata mua” roughly translates to “first” or “firstborn.” This painting recaptures the actual Eden of Tahiti, the genesis of the land. He paints his hut into the painting to explain to the viewer that he was meant to be a part of this land and culture. He refused to be a simple spectator but requested to be immersed. He felt this land was a part of him as he was of it. Also visible to the viewer is a sculpture of an ancient deity named Hina, goddess of the moon. This goddess was the mother of the earth god Fatou through that of the titan, supreme god; this trifecta of gods is directly tied to the land’s spirit of death and resurrection (Crepaldi, pg. 81). The ancient themes continue into the presence of ancient practices like the woman playing instrument called the “Vivo.” Combining ancient context clues, vibrant colors, and rejecting any source of Westernization, Gauguin can recapture the essence of the Tahitian Eden he has long sought after.

In his reality, being surrounded by so people in European fashion and culture in Papeete forced him to move once more to the remote village of Mataiea. Just a short thirty miles away, this area was untouched by the colonists and the Western ideals had yet to be an influence on the Natives. He rented out a small shack that faced the sea and the mountains on either side, depicted in his painting Matamoe (fig. 11) in 1892.

Figure 11

Similar to Mata Mua, Gauguin is depicting the rebirth of his new Eden. He writes of the moment in Noa Noa where he catches a young man chopping with an axe as if it were a dream sequence. The simplicity of this new lifestyle had taken hold of him as he thrived. From the edge of yellow, sandy shores to the mountain peaks in clouds above, Gauguin captures the essence of Tahitian beauty through his abstracted colors and blocked out compartmentalizing. This painting is a glimpse into the mind of someone living in pure bliss and contentment. He had finally escaped the world he so immensely detested and could live the primitivist life he always envisioned. He immersed himself into their culture: learning the language, eating the food, going barefoot. He wrote in his diary, “...little by little, step by step, civilization is peeling away from me..” (Hollmann, 24). He began his journey into the primitivist life he had longed for.

Among his attempts to become integrated with the people he called the Maoris, he met the thirteen-year-old Teha’amana, also known to as Tehura. Their non-binding marriage was arranged but never lacked the fervor and inspiration of love that he wanted out of a marriage. He elaborates on how “The gold of Tehura’s face flooded the inside of our abode and the surrounding countryside with joy and light...Tahitian paradise, nave nave fenua...And the Eve of this Paradise became more and more submissive and affectionate. I am permeated with her fragrance: noa noa!” Tehura was his muse during this time and a consistent model seen in his works. Having such strong emotional pulls from Tahiti itself and Tehura, Gauguin began painting with more euphoria and sensuality. He began pulling symbols and coloration from strictly his own internal experience versus being influenced by nature or people. This inspiration grew from his unconsciousness.

In the painting, Vahine No Te Vi or Woman with Mango (fig. 12), Tehura is modeling in an intimate and rather different painting for Gauguin. The land of Tahiti is not directly shown here and yet we are to associate the symbolism of the mango in hand as being native to the tropics. The mango is also a direct symbol for fertility and motherhood, which foretold Tehura eventually give birth to Gauguin’s child. Gauguin’s experience with religious or pastoral symbology correlates well to the royal purple of Tehura’s gown. She becomes almost saint-like in her role as a mother from such a “primitive” land.

We also see Tehura painted in another intimate format, but unclothed and on her bed. Manao Tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Watching) (fig. 13) depicts her fearing the spirits and ghosts haunting in the night. He places lights and shapes to mimic the movement of spirits to tie into the women’s terrified expression. He writes in a letter to none other than his first wife Mette mentioning how European women would never pose in such a manner, but these women would. He is astounded by the Tahitian women’s reaction to fear and is determined to retouch the scene for himself to convince us of that point. Gauguin’s works at the time continued to follow this trend of employing the local myths and religious stories to show the complexity that is held in this beautiful, spiritual land. Pieces such as Ia Orana Maria (fig. 14) and Arearea (fig. 15) house symbols of holy figures like the Virgin Mary and physical tokens dedicated to deities.

By the time these paintings were completed, Gauguin was running out of money and running out of time before he would have no choice but to be forced back to France where some stability remained. He also had a heart attack early on in his time in Tahiti and was growing weaker. Within two years of his residency, Gauguin would be forced to say goodbye to his personal utopia. Upon his return, his distaste for France grew stronger. His paintings of Tahiti were popularly rejected by artists and buyers; no one in Europe wanted to understand or appreciate his primitivist synthetism. He had one a source of hope lying in Anna la Javanaise, a Singhalese woman he met through mutual friends (fig. 16). He had unexpectedly returned to Pont-Aven with a broken foot, single once again, and hopeless. Poor, out of work and inspiration, he knew he must find passage back to Tahiti once more, never to leave again. By 1895, he had returned to the South Seas where he would not paint again for a long while and builds himself a live-in-studio in Punaania.

When he began painting again, he would solely focus on native woman, both nude and dressed, in a variety of settings such as The Noble Woman (fig. 17) or Two Tahitian Women (fig. 18). While he admired the women he spent time with and had a numerous amount of teenage “vahines” as his wives and mistresses, over his time spent in Tahiti, the way he illustrates them is not about the sake of their individuality, but for what they are. Upon his second and final trip to Tahiti, Gauguin was no longer looking for love but lust. He had experienced too great of a loss already in life and finally gave in to his more barbaric tendencies. His connection to lovers was no longer romantically inclined and his satisfaction would come from only his mind now. Gauguin believed “These are not specific human bodies; these are not individuals; they are symbols of a life of peace and harmony” (Walther, 85). The women are his paintings mean much more than just a native people belonging to a land, but symbolize the land itself. He uses the female body as a metonym for the natural world he dreams of, untouched by Westernization and colonization. His views on women’s bodies did not correspond with that of Western Europe (fig. 19). He writes in his journal Noa Noa: “Thanks to our cinctures and corsets we have succeeded in making an artificial being out of woman. She is an anomaly, and Nature herself, obedient to the laws of heredity, aids us in complicating and enervating her. We carefully keep her in a state nervous weakness and muscular inferiority, and in guarding her from fatigue, we take away from her possibilities of development.”

In saying this, Gauguin wishes for the renewed acceptance in a female body that has not been touched by societal expectations and Western ideals. The naturalness of a female body is at its purest state when left alone to nature’s will. He noted “I love women that are rounded and base. I mind it if they have a mind of their own, that kind of mind which is too mindful for me. I have always wanted a fat mistress and never found one. Mine have all been as flat as a pancake and the joke has always been on me.” Tahitian women were able to embody his vision for women in relation to their naturalness (fig. 20).

Within his journal Noa Noa, Gauguin had written notes on the body of the “savages’ he observed. Author Peter Brooks interprets his notes on Gauguin as being “...attracted to androgyny, which is a part of the animal ‘purity’ of primitivism while also part of its sensual appeal: it appears to liberate him from European categories of difference” (Pg. 67). He goes on further to explain that Gauguin’s journal exposed a bisexual nature among a certain chapter with a younger man. And while this exposes the comparison in female & male bodies of the Tahitian people, Gauguin chooses to dismiss the male figure in favor of the female body so that he can pursue the purest form. “The passage from Noa Noa becomes virtually an allegory of a large cultural need to center discourse of the body exclusively on the female body, as if the male body and the temptation of androgyny were too dangerous to handle” (Brooks, 67). To break down the barriers of Western standards and liberate himself, Gauguin needed to re-familiarize himself with women’s bodies in an objectifying manner.

The depiction of a woman’s body in Gauguin’s art is not intended to represent the woman for her unique self, but her physical entity. While Gauguin dedicated much of his work to the study of women and lived amongst them, the portrayal of these women are detached from the individual soul of a person but the soul of the land embodied in women. Much like the society of Tahiti, Gauguin strived to cleanse the people in front of his eyes and reimagine them as integrated with the Eden he expected. “The Eve of your civilized imagination makes young almost all of us misogynists...the Eve of primitive times who, in my studio, startles you now, may one day smile on you less bitterly.” Gauguin also writes “The Eve I have painted (she alone) logically can remain nude before our eyes. Yours in this simple state couldn’t walk without shame and, too beautiful (perhaps), would be the evocation of an evil and a pain.” His attempt at refamiliarization of the female body stems from tying her body back to nature herself, au naturel in nature, bringing back the beginning ages of primitivist life and away from any touch of civilization.

For Gauguin, his ideal woman figure was more that of an animal, beastly and untamed, “My chosen Eve is almost an animal; that’s why she is chaste although naked.” (Brooks, Pg. 64). And portraying an Eve in Tahiti as it was, clothed in Westernized garbs and acting civilized would do him no justice. Gauguin’s Eve is a nude woman who is a branch of nature herself. The Breton women had glimmers of hope for rustic, untouched lives but could not truly achieve the animalistic nature of Tahitian women in Gauguin’s eyes. Looking at Gauguin’s 1890 piece entitled Breton Eve (fig. 21) made before his time in Tahiti, we the viewer can see a shy woman, hiding her nudity with her body and use of a low hanging tree.

This Eve is that of one after sin has found a home in the Garden of Eden. She is ashamed of her animalism and bareness. Only two years later do we see works like his Exotic Eve (fig. 22) after time spent in his primitivist headspace. This Eve is out in the open, hiding nothing from nature with no consideration of shame because it is not ever been a thought in her mind. She stands out from under the tree, shading herself from no object and no person, the way art was before the fall of humanity. Gauguin’s symbolist nature takes form in this painting much stronger here; we see the serpent still existing and Eve yet to have eaten the fruit. We are to assume that this translates to a depiction of Eve before the fall of Eden; Breton Eve is an afterimage of Eve.

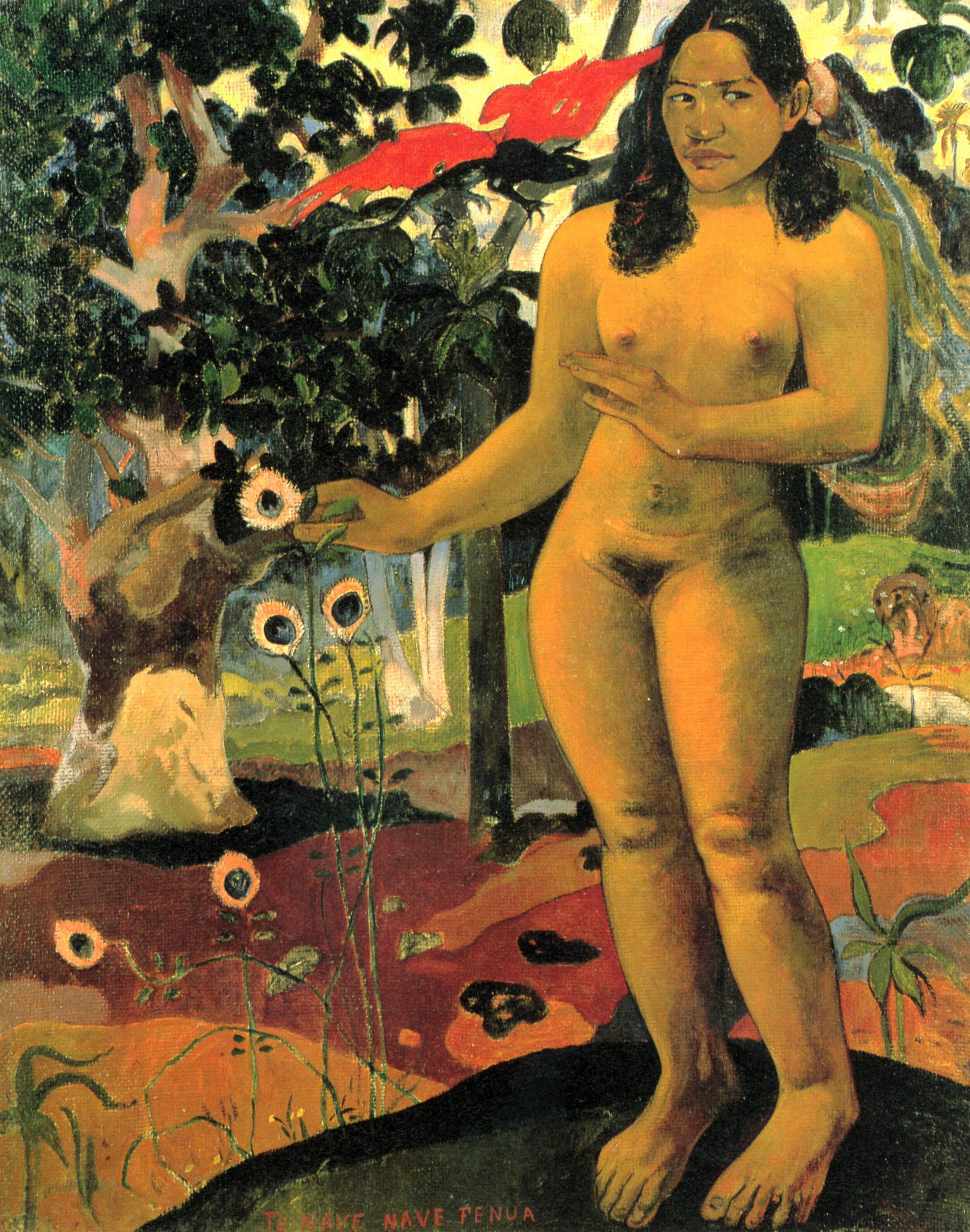

Figure 23

Gauguin's full vision of an exotic Eve comes to fruition in the painting Te Nave Nave Ferua (fig. 23) or Delightful Land. Gauguin’s wife Tehura models his new and improved exotic Eve, overtaking the canvas and forcing the viewer to comprehend her body. Her entire body fills the frame with his famous golden skin tones as if just birthed from the vibrant, lush nature leading behind and below her. Her body, within the frame’s space and perspective is touching every aspect of nature, from the ground she stands on, the birds and trees, up past the mountains into the sky. The shape of her body almost feels unnaturally proportioned and compacted in the frame. Her shoulders and hands appear too large for her body as well as her neck being rather compacted to the point of no visibility, disconnecting any natural flow from the body to the head. The skin tone in her face also appears to be darker, insinuating that this body is not truly human and can take the shape of any female. For lack of a better expression, she has become the elusive and shapeshifting “Mother Nature.”

She also stands there ready to pluck from the native flora, a peacock feather shaped flower of Tahiti, noted for being their interpretation of the Genesis forbidden fruit, mimicking the pose she holds in other past renditions. The serpentine symbol of this piece is portrayed as a red- winged lizard in the branches of the trees, eluding to this captured image to genuinely in Tahiti where lizards would be native. This is the Eve Gauguin aspires to achieve: she is curvaceous, young, unadulterated by the West’s touch. Before the fall of Eden, Gauguin captures his contentment and utter ecstasy in this “delightful land” that belongs to sacred Eve. This land is her’s and she is the land; Tahitian Eve is synonymous with untouched Tahiti itself. Eve is the representative of the soul and spirit that fills this land for she is not just a person standing in the forest. She is a physical deity of the land who represents primitivism and savage life Gauguin endeavors to discover.

Gauguin’s realization of Tahiti not being the place he imagined was mended by him symbolically placing women in nature as the essence of savagery. Gauguin renders women as a metonym for nature and the land of Tahiti. Simply painting a landscape could not capture the full spirit of the primitivism of Tahiti, but placing women into the painting brought back the soul and the spirit into his visual, Tahitian world. He said himself in an 1888 letter, “A hint—don’t paint too much direct from nature. Art is an abstraction; draw it out from nature while dreaming upon it and concentrate more on the creative process than on the result, that is the only way to come close to God, namely doing the same as our divine master, creating.” He creates a self-composed space of interaction between humanity and nature that fulfills his idea of a primitive image. One of his last great masterpieces to do so took steps toward integrating his own life through gospel motifs and every stage of life. And it remains one of his most famous pieces of work, Where Do We Come From? What are We? Where Are We Going? (fig. 24). Before his death, he wished to create this piece that would be the ultimate attempt at a philosophical message to attest to his life’s journey.

Figure 24

Within this painting, we see the stages of birth, life, and death, segmented into three implied sections within the composition. The phases go from right to left, starting with the phase of birth and adolescence with three women surrounding a sleeping baby and the other women in the background observing the choices of motherhood. In the center is a more obvious figure seen before from Gauguin of Eve picking the forbidden fruit, representing the moments before the sin of humanity where we transition into the left portion of the painting where we see death. Death is crouched in grey shadows with the figures that exude shame and sin. With every aspect he symbolically shares, Gauguin still does not wish to define the actions or human placement so that the vague mystery remains. His personal life and artistic goals never resolved themselves or felt complete so he intended to leave behind the ambiguity that life generally holds. What is highlighted through this ambiguity is the symbolic intention that his idyllic savage spirit is alive and thriving when shared between the unadulterated land and people. The solemn and stoic poses held by every character or feature amidst the radical color variation showing depth combine to force the viewer to consider the people almost as institutionalized parts of that landscape. They are inseparable from the land; they are created from the earth, live off of the earth, and will die and return into the earth.

While at the bitter end of his life, Gauguin paints so passionately so that his last major piece is his message to the world. He is begging all that see this art to return to the earth and abandon all sense of social pressures, to find the simple savage in their souls. He wishes not for the primitivist life to be neglected but to be exalted as the proper way of life. We are to return to his ideal savage lifestyle and abandon all semblance of Westernization through looking at this heavy, massive piece of work. This was his last claim to remind people that Tahiti was his idyllic Eden, with the “savage” natives treating the land in a properly “primitive” way, before any colonization. However, the reality was that Tahiti had been colonized and the West had invaded. He could not erase that so he had to imagine the Eden of his assumption and force “reality” into his art featuring the symbolic spirit of Tahitian women.

The women of Tahiti were enough for Gauguin to find the primitive spirit that remained in the land. They became his beacons of hope and through that, he essentially turned them into icons and idols of his savage Eden. Exotic Eve, Te Arii Vahine, Te Nave Nave Fenua, and Ia Orana Maria are all hailed as women figures that enrapture what it means to be primitive in Gauguin’s reality. Without the aid of the women as symbolic bodies of holiness, deities even, Gauguin would be at a loss to convince viewers that his Eden is the honest and appropriate utopia. It is due to his depiction of the women that his paintings hold so much power spirit and motivation. Painting an idyllic landscape could never hold the same impact as a primitivist portrait within the landscape. It is the culmination and gestalt of every aspect of Tahiti that forms Gauguin’s Edenic paradise.

Sources:

Amishai-Maisels, Ziva. “Gauguin's Philosophical Eve.” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 115, no. 843, June 1973, pp. 373–382.

Brooks, Peter, and Whitney Humanities Center. “Gauguin’s Tahitian Body.” The Yale Journal of Criticism, vol. 3, no. 2, 1990.

Crepaldi, Gabriele. Gauguin. Edited by Jo Marceau, DK Pub., 1999. Gauguin, Paul. Noa Noa: the Tahitian Journal. New York : Dover Publications, 1985. Hollmann, Eckhard, et al. Paul Gauguin: Images from the South Seas. Prestel, 2001.

Pichon, Yann Le. Gauguin: Life, Art, Inspiration. Edited by Nora Beeson, Harry N. Abrams, 1986.

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail, "Going Native: Paul Gauguin and the Invention of the Primitivist

Modernism," in Norma Broude and Mary Garrard, eds. The Expanding Discourse, New York, 1993.

Walther, Ingo F. Paul Gauguin, 1848-1903: the Primitive Sophisticate. B. Taschen, 2017.